✺

Abercrombie & Fitch used to publish a magazine called A&F Quarterly, the Fall 2003 issue of which features a series of image captions written by Slavoj Žižek. This special Back-to-School issue is subtitled the “Sex Ed Edition” and consists of sixty-two sun-drenched spreads of tan, athletic youths frolicking beneath the surface of Žižek’s trademark Lacanian aphorisms, which are rendered in red, black, and white block letters, all-caps. “Back to school” time, Žižek announces, means that one must “forget the spontaneous pleasures of summer sports, of reading books, of watching movies, of listening to music. Pull yourself together and learn sex.” From page to page, the boys and girls of A&F progress from a state of edenic SoCal semi-nudity to moody gazes out of nouveau-Victorian villas to a series of black-and-white softcore schoolroom scenarios. The magazine climaxes in several spreads of Dionysian festivities that look like a frat party crossed with a Venetian carnival.

If the revelation of psychoanalytic theory was that desire is constituted by lack, the revelation of Abercrombie & Fitch was that desire for clothing works the exact same way. Mostly, the models in A&F Quarterly Back-to-School: Sex Ed Edition aren’t wearing Abercrombie & Fitch; in fact, they’re not wearing anything at all. One particularly naked page has a long-haired, square-jawed surfer-looking guy with a big cross tattoo on his muscular bicep shimmying out of his cargo cut-offs. His crotch is artfully concealed by his thigh. The text on top reads: “THE OBJECT OF DESIRE IS HIDDEN BEHIND THE THIGH BUT THE TRUE CAUSE OF DESIRE IS THE TATTOOED CROSS ON THE ARM. IS IT NOT CLEAR THAT WE REALLY MAKE LOVE WITH SIGNS, NOT WITH BODIES? THIS IS WHY ONE HAS TO GO TO SCHOOL TO LEARN SEX.”

I have tried my best to learn sex. In fact, I have even read What IS Sex?, a book by another Lacanian philosopher, Alenka Zupančič. Zupančič takes a properly philosophical approach to her titular question, moving beyond the prevailing discourse that reduces gender to a “social construct” (Judith Butler et al) in order to elevate sex (as in, ‘female,’ not as in ‘sexual intercourse’) to an ontological and epistemological problem. Unfortunately, at the time of my reading, I was no longer in school. In my classes, professors had often cautioned us against bad, improper readings of books like Zupančič’s or Žižek’s, full, as they are, with seductively polysemous terms, language that is promiscuously close to our everyday vocabulary. For example, when Lacan says “there is no sexual relation,” you’re not supposed to think of your romantic failures…

But, reading What IS Sex? the summer after college, I totally did. In fact, I graduated from bad reading to something not much like reading at all. Like in an Ed Ruscha painting, letters began to curl at the edges, lifting off the page or sinking beneath it, gaining substance, color, and a subtle, shimmering movement. A GAP around which REALITY curves, a CHAIN of signifiers, a NON-RELATION, KNOTS… As the summer deteriorated along with my analytic mind, these words, which once held terminological specificity for me, floated gradually away from their contexts, becoming both increasingly vague and auratically dense, like the stylized lettering on graphic t-shirts. The terms associated themselves freely with inappropriate partners, other words and images having little to do with problems either ontological or epistemological. I experienced the book as though there was something like a ring of half-naked models dancing just behind the words on every page, stripping themselves of their meanings, tearing me from their concepts, and pushing me into the pool…

A&F Quarterly, Fall 2003.

But is it not clear that we really read with bodies, not with signs? There is a term for it: “figurative language.” Like the products sold by Abercrombie & Fitch, the figurative language suspending psychoanalytic theory is often textilic: “nets” of signification, “chains” of signifiers, “knots,” “rips,” and “tears.” The role of psychoanalysis, as Zupančič describes it, is to find the “right word” to unlock the “twisted logic” of the collection of linked meanings produced by the activity of free association. “The right word is not the right word by virtue of what it means, but by what it accomplishes.”

There are many ways of encountering words; not all of them involve reading meanings. There are many ways of making meanings, some of which are much like wearing clothing. This essay is a form-centric fan fiction for a body of thought that I love not only by virtue of what it means, but for how it looks and feels. And so, in the spirit of A&F Quarterly, here is a kind of non-linear and looping moodboard, a free associative lookbook for this, my favorite figure of language:

~ FABRIC OF REALITY* ~

*Because this is an attempt to invent a visual dream-logic around other people’s words, the connecting threads are “real” only in the sense of that phrase: of reality as something slippery, stylized, and easily torn.

* * *

In Chinatown last fall there was a billboard floating at the corner of Canal and Forsyth St: the words ONE OF THESE DAYS hanging in a baby-blue sky. It looked like a bad copy of certain Ed Ruscha paintings, in which words are often superimposed on landscapes of the American West. I think it was an advertisement for a streetwear brand by Matt McCormick, an artist who makes Ruscha-like Americana art (cars, cowboys, coca cola, etc).

Ed Ruscha, Not a Bad World, Is It?, 1984.

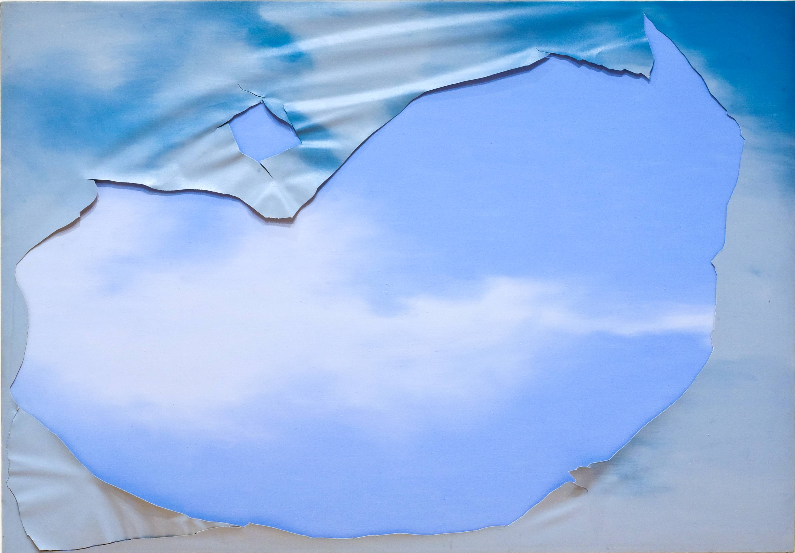

Many of Ruscha’s paintings rip language from advertisements, so the looping image-recycling-structure that landed his aesthetic on a fashion billboard is apropos. The Ruscha above, in which the word “world” vanishes into the blindingly bright horizon situated above a supernaturally beautiful lake and below a bank of pastel clouds, reminds me of Ruscha’s longtime best friend and collaborator Joe Goode’s Torn Sky series, in which a rectangular surface of sky is ripped open to show a different reality-layer of sky beneath it.

Joe Goode, Untitled, from the series Torn Sky Paintings, 1975-1976.

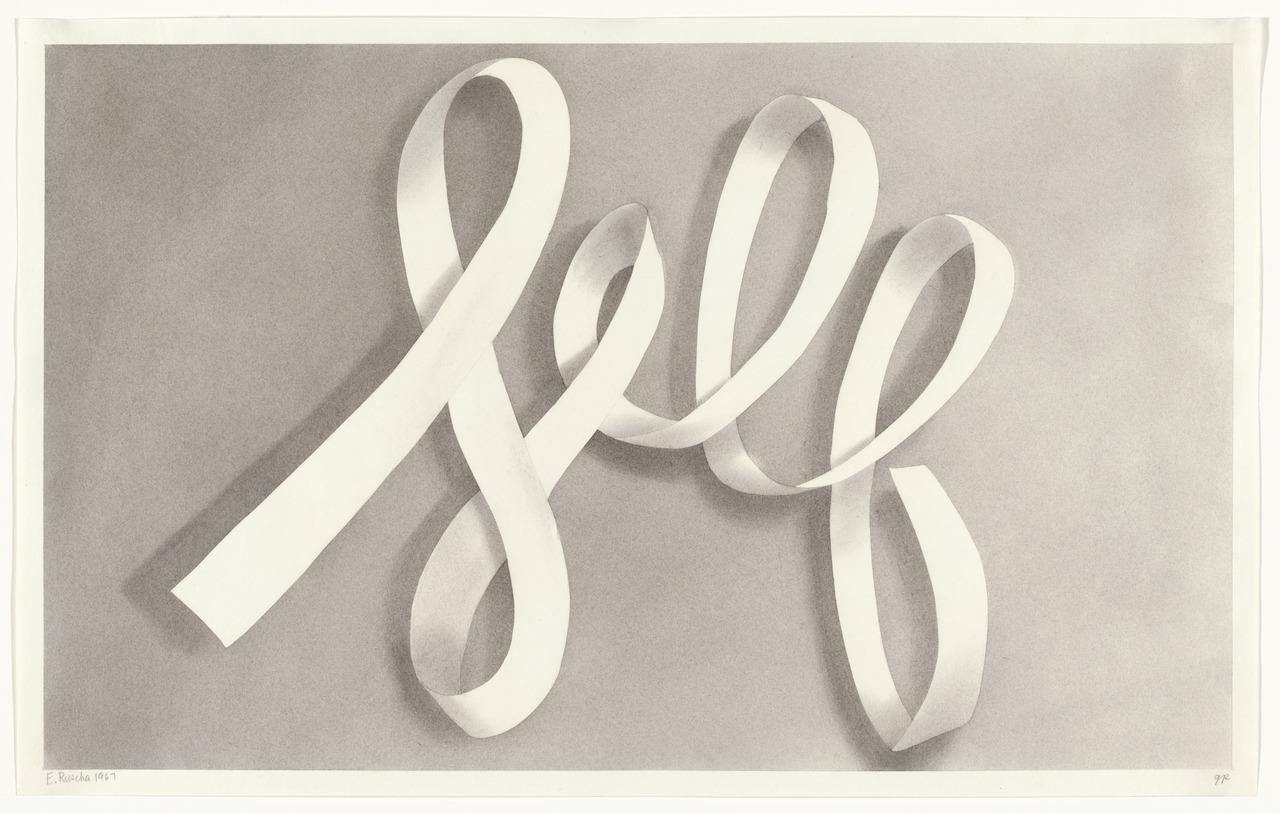

Goode’s hyper-, or rather super-realistic holes look more like tears in paper than fabric of reality, similar-but-different substrates of reality-producing-media. On an unfamiliar substrate, like canvas, a word is a different kind of tear: in this case, a tear in media-specific conventions. All my favorite Ruschas are about language appearing out of the blue. In Desire (1969), the title is spelled out as though by seafoam on the golden gradient of an Abercrombie beach, like Aphrodite washing up on the shores of Cythera. Another favorite Ruscha is Self, a delicately shaded pencil drawing in which the eponymous word is formed by the one area of the page unmarked by graphite—a constitutive absence curving and determining the space in which it appears: in this case, a pretty white ribbon hovering above a background that, though empty, is not blank. Self is a visual, and physical, instantiation of the language Zupančič uses to describe Lacan’s concept of the non-relation: the gap, or missing link, the tear in the fabric of reality that “dictates the conditions of what ties us”—like a ribbon—“which is to say that it is not a simple, indifferent absence, but an absence that curves and determines the structure with which it appears.”

Ed Ruscha, Self, 1967.

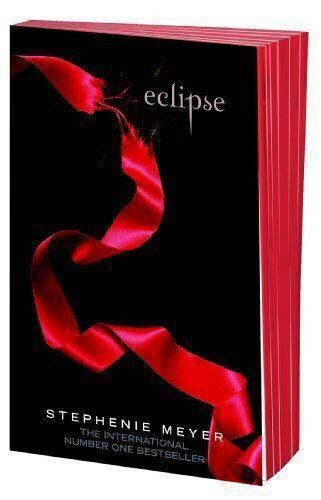

A looping ribbon also graces the cover of the third installment of Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight series. The Twilight book covers all show hallucinogenically lustrous red objects on a pure black, void-like background; most infamously, a dusky apple held in a pale pair of hands. For commercial children’s literature, they’re intoxicatingly abstract images: highly suggestive yet revealing nothing concrete, hinting and teasing...but at what?

I remember when the most popular girl in fifth grade brought Twilight to school one day: we crowded cautiously around her desk, approaching the thick volume like the monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Though we knew little of the plot, we immediately recognized that this was a dangerous story. After opening this book, there’d be no going back. So we didn’t read it. Not at first. We just touched the cover, leaving sweaty fingerprints all over its glossy surface.

The knots and signifying-chains of psychoanalytic theory have always reminded me of knitting. The summer I read What is Sex?, I lived with five other girls, all of whom studied either painting, fashion, or textile design. One of my then-roommates, Anna Armstrong, knits fabrics that often either incorporate literal holes, voids in the garment, or play with lesion-like swathes of lighter or darker-colored yarn: filaments of the same reality/medium as the rest of the pattern, forming a ground that both tears through and sinks beneath itself. The holes left behind are almost optically-illusionistic, like Goode’s Torn Sky. In her take on a pleated skirt—a staple of Abercrombie & Fitch prep-wear—the folds in the cloth become holes: highly tactile tears out of which spill a looping growth of ribbon.

Skirt by Anna Armstrong

This skirt reminds me of the iconic pleated miniskirt from the Spring/Summer 2022 Miu Miu collection, which features lots of Abercrombie-like country-club-wear: skirts and trousers in gray and white and navy and taupe, also cable-knit sweaters and button-downs, all of them severely cropped. Like Armstrong’s skirt, the hems are raw-edged, with threads hanging down, as though the fabric has been torn straight off.

Miu Miu S/S2022

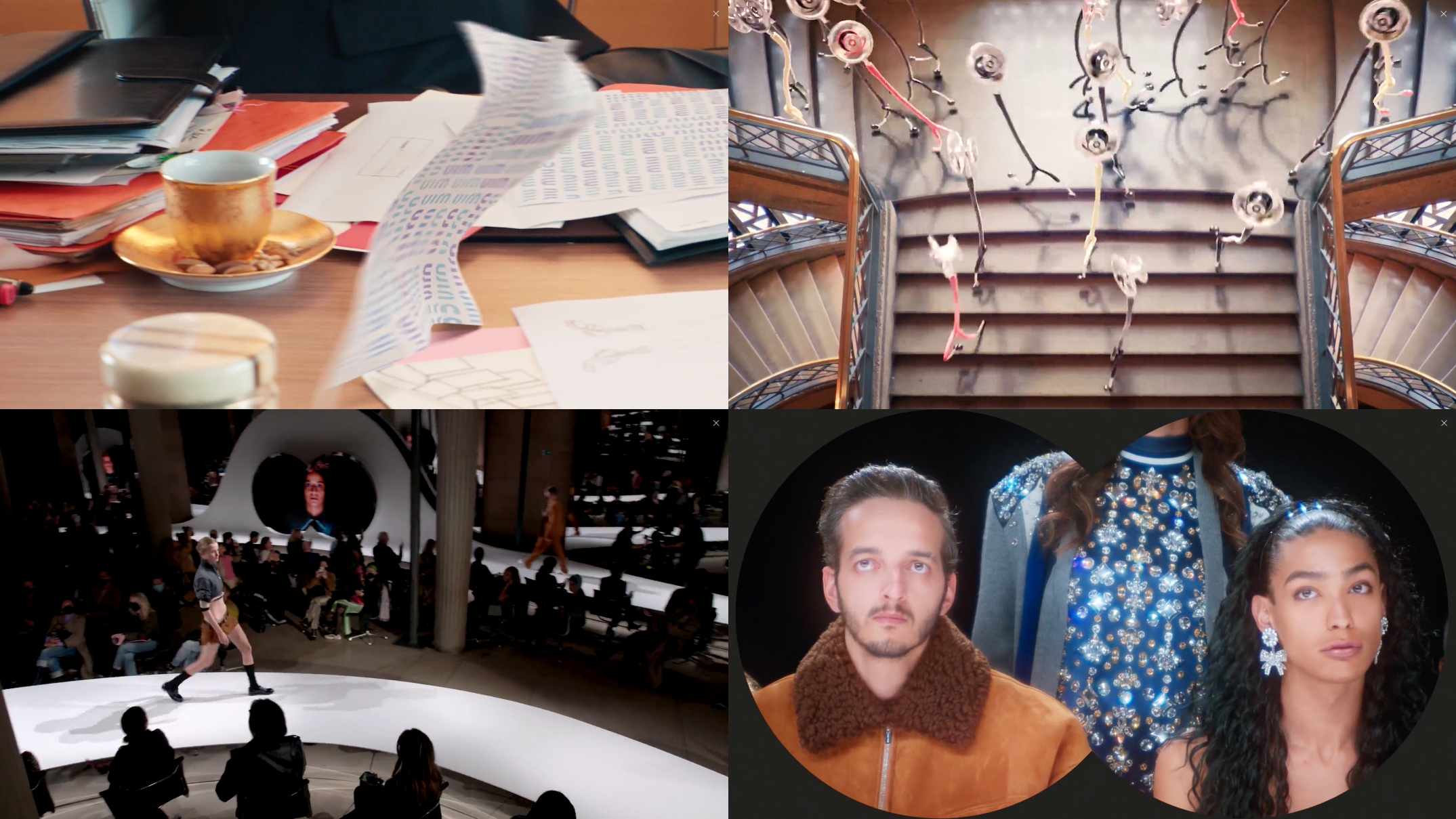

Sex is a big word for Miu Miu. The brand’s clothes, according to the Prada Group’s website, are simultaneously “sensual and intellectual,” an effect they have achieved by “transforming fashion into a mental state.” And, based on the video that serves as a kind of prologue to the Spring/Summer 2022 runway show, the mental state of Miu Miu is quite strange. It goes something like this:

Through binocular lenses, we see a hallway; in it, a middle-aged woman. Her office worker ensemble is accentuated by strappy silver sandals. Colorful leaves of paper flutter out of her black Miu Miu briefcase. “Where are you going?” she says to the papers, in (I think) Moroccan Arabic (English captions are superimposed); we cut to an animation of what appears to be an anthropomorphized stethoscope dancing under strobe lights. The woman dances down the hallway to techno music, sits down, and takes a call: “My brain feels like a pressure cooker!” Her papers, most of which are covered with the words MIU MIU printed over and over in purple and blue ink, keep trying to walk off her desk… Now, a gleaming stethoscope, apparently naked, squeezes into a squeaky rubber casing—its clothes? Hordes of stethoscopes rush down a grand staircase, then down the runway. The audience is shocked! They sit in Eames chairs. iPhone cameras flash. Finally, a model materializes on the catwalk, which winds through the audience in a white ribbon shaped exactly like Ruscha’s Self. For the remaining ten minutes, the show proceeds more or less uninterrupted by stethoscopes or other non-models, except for a brief clip of some women discussing the Moroccan affinity for ass lifts. At the end, Miuccia Prada herself appears, like a fairy godmother, for only half a second, dressed all in red. Red is a color that wants, more than any other, to be interpreted; hence its use on the Twilight book covers.

Miu Miu S/S2022 runway video by Meriem Bennani

Watching this video—created by artist Meriem Bennani, who also oversaw the installation of the runway show—is like being implanted in someone else’s dream: an idiosyncratic, highly personal collection of associations (in fact, the office worker at the beginning is Bennani’s mother). Like dreams, the images are disturbingly hypnotic; like dreams, they beg interpretation. The field of psychonalytic theory was in large part founded on interpretations of dreams; so was the Twilight franchise. The idea for the first book famously came to Stephanie Meyer at night, in a vision of a boy and a girl lying in a magical meadow carpeted with purple flowers: a landscape is reminiscent of Ruscha’s Not a Bad World, Is It?

Screenshot of the YouTube page of a fan video made for the score for Twilight

The unbreachable gap between human Bella and vampire Edward feels very Lacanian: Bella is the only person in the entire world whose thoughts Edward cannot “read” (he is telepathic), which is why he is obsessed with her. The best he can do is close looking—for example, by climbing through Bella’s window at night to watch her sleep. This kind of opacity to being-read is essential to sex. More recently, Žižek has ranted extensively on the dangers posed to love and fantasy by Neuralink, the nonexistent software envisioned by (curiously vampiric) Elon Musk that would enable telepathy, eliminating the gaps, tears, and missed connections caused by language. (Appropriately enough, Musk and his girlfriend, Grimes, are more or less separated.)

The fraying red ribbon twisting across the cover of Eclipse might symbolize not only the unraveling of protagonist’s Bella’s reality, which is populated by supernatural, violent creatures, but also the infinitely more distressing experience of romance (in book three, Bella must finally choose between werewolf Jacob and vampire Edward).

~ “There is no sexual relation…” ~

The most striking cinematic realization of a sexual non-relation manifesting as a rip or tear appears in Where the Heart Is (2000), another tale of innocence lost. Here, pregnant teen Natalie Portman is taken for a ride in her deadbeat boyfriend’s car. There’s a gaping hole in the floor of the vehicle, exposing naive Natalie to the cruel world racing by beneath her feet. She loses her flip-flops in the gap. While shopping to replace her shoes, her boyfriend abandons her at the Walmart. As with Twilight, non-reading plays a central role in the romance: in typical star-crossed fashion, Mr. Right turns out to be a brilliant, scholarly librarian, whereas Natalie’s character is near-illiterate. Because of this charming incompatibility, we know they will be married.

Where the Heart is (2000), dir. Matt Williams.

Because it was lockdown the summer I took it upon myself to learn about sex, living in the house with five girls was a lot like situation in The Virgin Suicides. In Sofia Coppola’s adaptation of that book, Lux writes the name of her crush on her underwear in Sharpie. This is revealed to us by the appearance of a momentary hole-like transparency in the cloth of her prairie dress. Like in a painting by Ruscha, the word has blazed not only through the floral fabric, but through the reality effect of the film itself.

The Virgin Suicides (1999), dir. Sofia Coppola

Such rips and tears in fabric are, of course, ubiquitous in fashion. Distressed denim is a favorite of sexually active teens.

© Mozhjeralena / Adobe Stock.

* * *

The Spring/Summer 2022 Miu Miu collection is accessorized by an enigmatic description of the clothing that begins: “A reaction to and a reflection of reality, an economy, a freshness found in iterations of eternal, universal garments.” How to read this sentence, other than as a moodboard of dream-language and concepts, tenuously connected by commas? If Miu Miu is fashion as a mental state, this language is a mental dream-state as fashion. The purpose of advertising is ostensibly to create a fantasy world so desirable that the reader wants to live in it. But this copy doesn’t imply a world or a narrative at all; like the images considered here, it is devoid of characters, or even emotions. If the sentence evokes anything, it’s abstractness itself. If it makes me desire anything, it is language itself. The fabric of reality it conjures is very thin, very transparent: little more than a hazy aura of the romantic sublime, with the invisible pattern of a Platonic ideal. Perhaps this is what the Abercrombie boys were dressed in.

That clothing has a kind of invisible, immaterial dimension which functions as a vector for desire is a favorite adage of psychoanalysis (the stocking as fetish object, etc). In a 1909 paper given to the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society, one of his first investigations of clothing fetishism, Freud describes the case of a man pathologically obsessed with fabric, and the fashion choices of his lovers:

“In this patient something similar to what took place in the erotic domain occurred in the intellectual domain: he turned his interest away from things onto words which are, so to speak, the clothes of ideas; this accounts for his interest in philosophy.”

Olivia Kan-Sperling is an editor and a writer living in New York. She is the author of Island Time, a modernist virtual world music video novella starring Kendall Jenner. You can listen to a discussion of this essay on Contain podcast, here.